RECOMMENDED VIDEOS

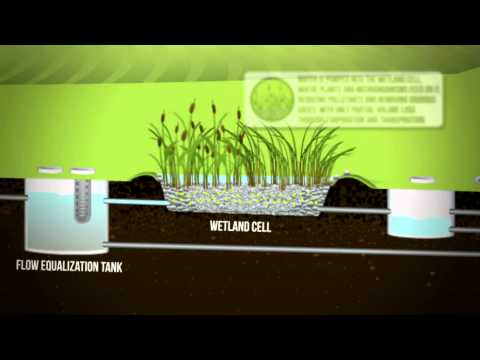

Eco-Friendly Wastewater Treatment System

FRANC Environmental, Inc.

Bukit Tagar Sanitary Landfill by KUB-BERJAYA ENIVIRO

KUB-BERJAYA Enviro Sdn Bhd

Promise Earth : Composting Machine Turn Organic Waste To…

Promise Earth (M) Sdn Bhd

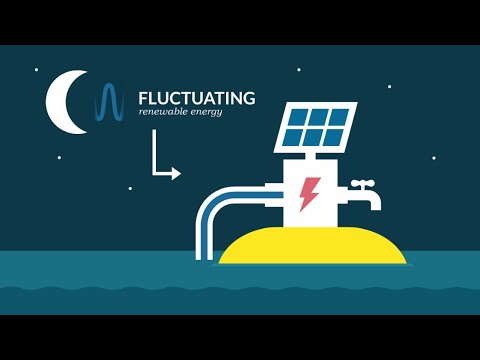

Elemental Water Makers, desalination driven by renewable…

Elemental Water Makers B.V.

Hyva Group Introduction

HYVA (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd

Related Stories

First paper straw factory in decades to open as UK bans plastic

Beach plastic audit in the Philippines reveals which businesses are the worst polluters

Made from sewage, these “popsicles” reveal the scale of Taiwan’s water pollution

World’s first mobile recycling plant turns trash into tiles

Air pollution is the leading environmental cause of death worldwide

06 Sep, 2016

Japan’s $320 Million Gamble at Fukushima: An Underground Ice Wall

Resource Recovery & Environment Management | JAPAN | 06 Sep, 2016

Published by : Eco Media Asia

FUKUSHIMA DAIICHI NUCLEAR POWER STATION — The part above ground doesn’t look like much, a few silver pipes running in a straight line, dwarfed by the far more massive, scarred reactor buildings nearby.

More impressive is what is taking shape unseen beneath: an underground wall of frozen dirt 100 feet deep and nearly a mile in length, intended to solve a runaway water crisis threatening the devastated Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station in Japan.

Officially named the Land-Side Impermeable Wall, but better known simply as the ice wall, the project sounds like a fanciful idea from science fiction or a James Bond film. But it is about to become a reality in an ambitious, and controversial, bid to halt an unrelenting flood of groundwater into the damaged reactor buildings since the disaster five years ago when an earthquake and a tsunami caused a triple meltdown.

Built by the central government at a cost of 35 billion yen, or some $320 million, the ice wall is intended to seal off the reactor buildings within a vast, rectangular-shaped barrier of man-made permafrost. If it becomes successfully operational as soon as this autumn, the frozen soil will act as a dam to block new groundwater from entering the buildings. It will also help stop leaks of radioactive water into the nearby Pacific Ocean, which have decreased significantly since the calamity but may be continuing.

However, the ice wall has also been widely criticized as an expensive and overly complex solution that may not even work. Such concerns re-emerged this month after the plant’s operator announced that a section that was switched on more than four months ago had yet to fully freeze. Some also warn that the wall, which is electrically powered, may prove as vulnerable to natural disasters as the plant itself, which lost the ability to cool its reactors after the 45-foot tsunami caused a blackout there.

The reactor buildings are vulnerable to an influx of groundwater because of how the operator, Tokyo Electric Power Co., or Tepco, built the plant in the 1960s, by cutting away a hillside to place it closer to the sea, so the plant could pump in water more easily. That also put the buildings in contact with a deep layer of permeable rock filled with water, mostly rain and melted snow from the nearby Abukuma Mountains, that flows to the Pacific.

The buildings managed to keep the water out until the accident on March 11, 2011. Either the natural disasters themselves, or the explosive meltdowns of three of the plant’s six reactors that followed, are believed to have cracked the buildings’ basements, allowing groundwater to pour in. Nearly 40,000 gallons of water a day keep flooding into the buildings.

Once inside, the water becomes highly radioactive, impeding efforts to eventually dismantle the plant. During the accident, the uranium fuel grew so hot that some of it is believed to have melted through the reactor’s steel floors and possibly into the basement underneath, though no one knows exactly where it lies. The continual flood of radioactive water has prevented engineers from searching for the fuel.

Freezing a Wall

To prevent groundwater from entering the damaged reactor buildings of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, engineers are pumping supercooled brine through pipes in the ground to form an underground wall of frozen dirt 100 feet deep.

Source: Tokyo Electric Power Company. Image by TerraMetrics via Google Earth

By The New York Times

Since the accident, five robots sent into the reactor buildings have failed to return because of high radiation levels and obstruction from debris.

The water has also created a waste-management nightmare because Tepco must pump it out into holding tanks as quickly as it enters the buildings, to prevent it from overflowing into the Pacific. The company says that it has built more than 1,000 tanks that now hold more than 800,000 tons of radioactive water, enough to fill more than 320 Olympic-size swimming pools.

On a recent visit to the plant, workers were busily erecting more durable, welded tanks to replace the temporary ones thrown up in a hurry during the early years after the accident, some of which have leaked. Every available patch of space on the sprawling plant grounds now appears to be filled with 95-foot tanks.

“We have to escape from this cycle of ever more water building up inside the plant,” said Yuichi Okamura, a general manager of Tepco’s nuclear power division who guided a reporter through Fukushima Daiichi. About 7,000 workers are employed in the cleanup.

Article by Martin Fackler

Read the full article at The New York Times